“Play” Is a Right, and Also a Power | Children’s Day Special Feature: How PlayPower Generates Well-being for Children

- echofline

- Jun 30, 2025

- 19 min read

1. The History of Children’s Playgrounds: From the Industrial Revolution to Urban Exclusion

“Playing was originally not a right of children.”

1. 1 In the Era without Playgrounds: Children in Factories, Not on Slides

In our eyes today, playgrounds are the joyful corners that children deserve. But 200 years ago, children’s “playgrounds” were coal mines, textile mills, and farm fields.

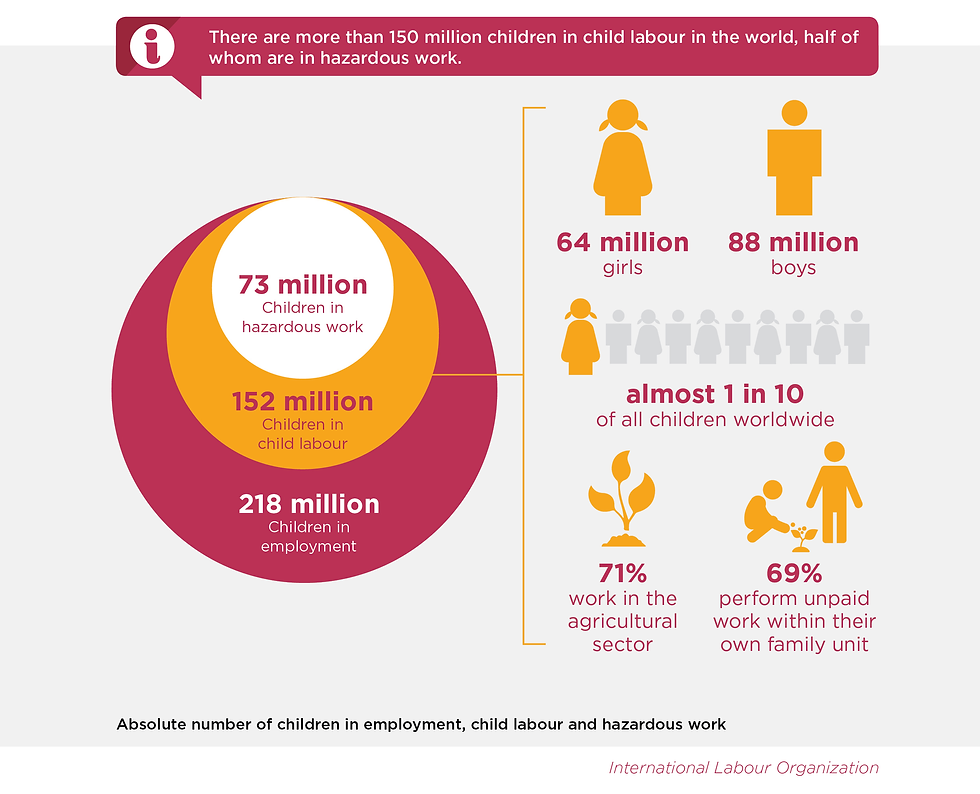

During the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, children were widely used as “cheap labor.” Many factories employed children under fourteen to move yarn and clean machinery—not as “parent-child experience” activities, but as high-intensity work exceeding twelve hours a day, with little rest and no safety guarantees.

It was not until the early 20th century that the child-labor system began to be gradually abolished. Thus, some conscientious reformers began to advocate: “If children cannot return to the fields, there should at least be a place for them to ‘properly’ play.” In 1885, Germany built the first “sand playground,” and soon Boston, USA, followed suit by establishing similar public play areas.

Originally, playgrounds were in fact a form of “pacifying design”: an “exclusive corner” set up for children with nowhere else to go in industrial cities.

Seward Park Playground (New York City)

Opening Date: October 17, 1903

Location: Seward Park, Lower East Side, Manhattan, New York City, USA

Background: This was the first permanent public playground built by a municipal government in the United States, marking the official provision of dedicated play spaces for children by cities.

Facilities: Including a cinder surface, fences, pavilions, children’s play and gymnastic equipment, and a large track surrounding the play area and children’s garden.

The establishment of Seward Park Playground reflected Progressive Era reformers’ emphasis on children’s right to play. In a 1903 letter about its opening, the renowned social worker Lillian D. Wald wrote: “...in municipal history, the rights of children are placed first for the first time.”

In October 1903, on a rainy afternoon, New York City’s first municipal playground opened in Seward Park in the Lower East Side.

Twenty thousand children instantly swarmed the site—climbing onto roofs, overwhelming the police, and eventually crashing into the playground. As soon as the mayor arrived, they rushed his car. The planned ceremony was canceled, and reporter Jacob Riis abandoned his speech, only wishing to get the children out of the rain. The mayor told those around him the now-widely quoted words: “Children have a right to play, just as they have a right to work.”

PlayPower HappyPower originated from the “Wall-Free Playground.”

When we built the first zone of the Wall-Free Playground, we witnessed firsthand how passionate children are about “playing.” This zone was in Binlian Xincun, Haikou—a typical urban village with no public spaces designed for children. The places children could play were extremely limited, even including dangerous construction sites. So when the play equipment appeared, the children of the entire urban village rushed out as if they had caught a signal.

From dawn until eleven or twelve at night, the children hardly stopped. Some pieces of equipment could only accommodate a few at a time, and queues averaged twenty to thirty people, yet they were still willing to wait—sometimes queuing multiple times—just to play again.

That zone was the first pilot of the Wall-Free Playground, and it was there that we first felt that “play” is one of children’s most instinctive and strongest needs.

1.2 Children’s Play Spaces in China: From Hutongs to Work-Unit Courtyards, to “Planned Childhoods”

In modern Chinese history, children have also been widely drawn into labor—whether in rural fields, textile mills, or in front of today’s live-streaming cameras—their “labor power” has often been rationalized, while the right to “play” has long been absent.

In traditional Chinese agricultural society, children’s participation in labor was common, especially in rural areas.

From a young age, children helped their families herd cattle, cut grass, transplant rice seedlings, cook, and look after younger siblings.

This “labor” was often not called “child labor,” but was part of the family’s collective survival mechanism.

In the early Republic of China, when modern industry first arose, there were also cases of factories employing child labor, particularly in coastal and industrial cities such as Shanghai, Tianjin, and Wuhan.

Newspapers such as Shenbao and Dagongbao repeatedly exposed the abuse of child labor in textile mills and coal mines.

Some factories hired 8–12-year-olds as “machine operators’ assistants” or “small porters,” paying low wages for long hours.

From the 1950s, the state began implementing compulsory education and explicitly prohibited the employment of children under sixteen.

Laws such as the Labor Law and the Law on the Protection of Minors explicitly stipulated no use of child labor.

But in practice, the imbalance between urban and rural development and uneven distribution of educational resources has led to certain “hidden child-labor” phenomena.

Child laborers during the Republic of China

Hidden Child Labor:

Left-behind children participating in household labor

Many rural children, left behind when their parents went out to work, took on the tasks of caring for younger siblings and farming at an early age. Although this is not formal “child labor,” they indeed shouldered labor responsibilities beyond their age.

Dropping out of school to work

Some teenagers (13–15 years old) in remote areas, due to family poverty, dropped out of school to work in small factories, restaurants, and car washes. Surveys show that in some urban villages, employed minors can still be found.

“New-type child labor” under the live-streamer, child star, and influencer economy

With the rise of the traffic economy, some minors are arranged to live-stream for long hours, shoot short videos, and participate in commercial endorsements. This behavior walks the line between legality and exploitation, sparking new controversies over “digital-age child labor.”

In traditional Chinese society, children’s play spaces mostly existed in gaps within nature and the community.

In past villages and urban hutongs, children’s play spaces did not come from dedicated designs but were self-made realms: a tree, an alley, a patch of ruins—each served as a natural playground.

“Playing doesn’t rely on equipment; it relies on open space and companions.”

By the mid-20th century, after the founding of the People’s Republic, the work-unit residential structure gradually shaped new children’s play spaces: the work-unit courtyard became the main stage for children, where rolling iron hoops, jumping rubber bands, and doing somersaults became collective memories for a generation.

Play in the Hutongs

Playing “Drop the Handkerchief” on the Open Grounds

It was not until after the Reform and Opening-up that Chinese cities began rapid construction, commercial centers emerged, and residential compounds became gated, gradually marginalizing children’s spaces in the city. More and more parents worried about safety, and play shifted from “outdoor free exploration” to “indoor training courses.”

“Play became ‘controlled consumption,’ and playing became ‘the gap between tutoring classes.’”

In recent years, with urban renewal and the introduction of the child-friendly city concept, governments and social organizations have begun to rethink children’s place in the city: from “functional corners” to “spatial protagonists.”

Sanya Haitang River Nature Exploration Park

1.3 After Urban Modernization, Children Are “Planned” Out of Their Living Circles

Let us shift to a broader perspective:

As cities develop—with roads widened and skyscrapers and shopping malls rising one after another—children’s activity spaces have been gradually squeezed.

When urban planners draft their blueprints, they rarely ask: “Where do children play?”

Or: “Do adults really no longer play? Do they no longer need to play?”

In modern cities, play has become a strictly “scheduled” activity: on the slide tucked into a corner of a residential compound, in training camps booked during holidays, within designated “safe zones.” Play can only occur at “specified times” and in “specified places,” making free play a “scarce resource.”

Many urban researchers point out that children are becoming “invisible” in public spaces—not because no one cares about them, but because the entire logic of the city has long since excluded them. Scholar Tim Gill argues, “A city that works for children is a city that works for everyone.”

But the reality is this: the children’s sections in malls increasingly resemble “care zones,” designed to reassure parents so they can shop, rather than to let children explore freely. Although newly built residential complexes may have “playgrounds,” they are essentially standardized equipment copied and pasted with rigid designs, often failing to consider the differing needs of children of various ages, nor incorporating inclusive designs for neurodiversity.

Some researchers even bluntly state: “Children in modern cities are almost systematically expelled.”

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) proposed the “Child-Friendly Cities” framework in 2018, noting that the vast majority of cities have failed to consider children’s needs, especially in terms of public spaces and participation mechanisms.

Tim Gill (advocate for children’s play rights), in his book Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities, emphasizes: “A city that is suitable for children is a city that is more friendly for everyone.”

A study by the Amsterdam municipal government in the Netherlands found that, over the past 20 years, children’s average daily outdoor free-play time has decreased by 40%. In the United States, children today spend 90% less time playing outdoors than their parents did.

Return to the 19th Century: What Did the Earliest Playgrounds Look Like?

Long ago, children did not have “dedicated venues” for play; they could run freely in city corners, pick up discarded objects, and build their own small worlds. But rapid urbanization brought challenges: crowded living environments and a lack of safe outdoor activity spaces posed great challenges to children’s development. Against this backdrop, playgrounds emerged. They advocate providing specialized spaces for children—not only for entertainment but also to cultivate healthy bodies, social skills, and team spirit through play.

Judging from the swings, balance beams, and rings in the photographs, the play equipment at the time was simple yet full of challenges, requiring children to use both hands and feet to train their coordination and strength. Especially the rings—this classic piece of playground equipment was already a favorite of children in that era. Here, children could not only exercise their bodies but also experience the sense of achievement from overcoming difficulties and boosting their confidence.

In 1946, at the Emdrup Children’s Playground in Copenhagen, children played with simulated tanks.

1.4 Play Is a Right, Not a Reward: Article 31 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

In 1989, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child, in which Article 31 states:

“Children have the right to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to their age.”

It sounds perfectly natural—who would disagree that “children have a right to play”? Yet reality often tells a different story.

In today’s world, too many children’s childhoods are squeezed down to school schedules and check-ins: waking early for classes, remedial lessons after school, weekend training sessions. The so-called “play” has become an accessory under a “reward mechanism”: only those who perform well can play; only when homework is finished can they play. Safe venues, ample time, and free play without adult intervention have virtually become an elusive dream.

In more severe contexts—such as children in war, disasters, poverty, or displacement—even basic survival is hard to guarantee, let alone play. Their “playgrounds” might be a patch of open ground amid ruins or outside refugee camps. According to UNICEF, over 400 million children worldwide live in conflict- or disaster-affected areas, and the vast majority of them are systematically deprived of their right to play.

The International Play Association (IPA) points out that although the Convention on the Rights of the Child clearly guarantees the right to play, the word “play” is often marginalized in policy discussions, urban design, and family decisions. Parents focus more on academic performance, governments prioritize subways and parking lots, and schools want children to “behave and be quiet,” thus, play gets “quietly excised” in countless decisions.

But in fact—

“We often say that children are ‘playing,’ but actually they are seeking ways to interact with the world.”

Play is not idle mischief, nor merely an outlet for emotional release. It is a hands-on way of learning—a process by which children engage their whole being to explore the world, understand social rules, experiment and reconstruct through trial and error, and build relationships. Role-playing, building, chasing, and cooperation in games are all simulations and rehearsals of “human society.”

Depriving a child of the right to play is not just taking away some fun, but stripping them of the opportunity to become a “whole human being.”

The Four Freedoms of Play

Scot Osterweil, Creative Director at the MIT Education Arcade, first proposed the “Four Freedoms of Play,” freedoms we may not experience outside of play:

1. Freedom to Experiment: The opportunity to try things—creative and exploratory—perhaps attempting things that may seem a bit crazy.

Some experiments are things that make adults shudder—such as physical challenge activities on the playground—while others are smaller in scale, like inventing a new game with the playground ball.

2. Freedom to Fail: This is a necessary corollary of the first freedom, because true creativity and experimentation may not yield expected results. This is crucial, for children who feel they are being watched and judged behave entirely differently than they do when they feel unobserved. Believing that failure will not bring permanent negative consequences allows children to think outside the confines they see in daily life.

3. Freedom of Identity: The ability to choose to be someone else during play. While this identity play indeed includes role-play (for example, “I am the little sister, you are the big sister”; “I am the dragon knight, you are the monster king,” etc.), it can also be more metaphorical—like a usually shy child taking on a leadership role during play.

4. Freedom of Effort: No one scores you based on whether you “tried your best” in the game. Unlike the “real life” adults are familiar with, minimal engagement today and lower energy tomorrow are not penalized.

2. The Blind Spots of Today’s Playgrounds: “Safety Cages” Controlled by Adult Logic

“Uniform playgrounds are, in fact, manufacturing uniform childhoods.”

Walk into a city’s standardized playground, and we can almost predict what we’ll see: plastic slides, small swings, soft mats, bright colors—but single-function equipment.

These supposedly “child-oriented” spaces are, in fact, rarely child-led. They resemble theaters crafted by adults for a “controllable order,” with children merely cast as actors permitted to “play by the rules.”

The Chinese-Style Playground: No Faults, but No Soul Either

In China, most playgrounds we take for granted—whether in shopping malls, scenic spots, schools, or residential compounds—present a “looks-fine but is-problematic-everywhere” state: cookie-cutter designs, dull and conservative aesthetics, standardized equipment layouts, making these venues feel like “copied templates” rather than play worlds truly tailored for children.

They emphasize “safety,” but at the cost of rounding edges and dulling stimuli, compressing the space for children to explore, fall, and experiment. They lay out paths, yet offer no freedom for children to choose their own routes. They fill the area with equipment, yet lack the “human traces” where graffiti, stories, and laughter can linger.

They assume adults “do not play,” and ignore the potential interactions between carers and the community.More importantly, most playgrounds have virtually no “cultural context”: no stories of Chinese children, nor any local expression of specific neighborhoods.

Children’s spaces have become depersonalized, de-emotionalized consumer installations, placed at mall corners, scenic spot exits, housing-estate atriums—used once and quickly forgotten.

This is not the fault of any individual designer, but the consequence of treating “play” as an accessory rather than as a public right. When play loses the possibility of creation and the entry point to co-shaping, the so-called “play space” truly becomes nothing more than “space.”

The biggest blind spot in most modern playgrounds worldwide is not that there aren’t enough or “cool” facilities, but that they ignore children’s right to autonomous play.

Within the design logic of urban public spaces, play seems to have become an “arranged” activity: in specified venues, at set times, following rules, avoiding danger—as if completing a “permitted task” rather than experiencing free growth.

But true play isn’t always “tidy” or “orderly.” Autonomous play means allowing children to daydream, fail, take risks, explore, and build their own orders; it also means giving them the freedom to fall, the right to play outside the instruction manual, and the chance to create chaos, conflict, and reconciliation.

PlaygroundNYC, a playground where children play freely.

Many so-called “safe” play facilities actually use adult fears to limit children’s possibilities, transforming play into a “safety cage.”

Child wants to climb a bit higher? No, it’s dangerous;

Wants to dig a hole in the mud? Too dirty;

Wants to pretend the slide is a battleship? Please use the slide according to the manual.

And this single-track, “safe,” closed-off design logic is doubly exclusionary for neurodivergent children, children with disabilities, and young girls.Already marginalized in public spaces, they find it even harder to enter, integrate, and feel a sense of belonging amid one-size-fits-all equipment designs.

At the root, the problem lies at the starting point of design: playgrounds are still products decided, planned, and approved by adults. Children have almost no chance to participate in the design and imagination of these spaces; their voices, needs, and interests are buried under pages of bidding standards and acceptance criteria.

The result is: we think we have given children a playground, but have in fact only drawn a visible-boundary “safety circle” for them.

PlaygroundNYC

On Governors Island in New York State, there is a playground called play:groundNYC, known as an “adventure playground”: there are no adults-designed slides or swings. Instead, it’s a chaotic free-build zone with hammers, planks, ropes, tires, old furniture, and more.

Here, children build their own slides, towers, and secret bases. There are no “no climbing” signs—only adults called “Playworkers” who quietly observe and intervene only when necessary.

Here, children are not “using” playground equipment; they are constructing their own world. Their bodies move, and their imagination, communication skills, and conflict-resolution abilities are all running at full speed. Play:groundNYC attracts tens of thousands of children each year. It is considered a powerful rebuttal to standardized playgrounds and a spatial experiment in “de-adult-centring.”

3. Playgrounds from Children’s Perspective: Arenas of Growth, Participation, and Connection

“A truly child-friendly space makes children not just users, but designers, organizers, and storytellers.”

Traditional playgrounds treat children as “service recipients,” but a playground seen from children’s perspective means a complete role reversal. Children are not merely “users” who come to play or stroll—they become the true “owners of the space,” able to propose ideas, take part in construction, and leave their marks.

In education, play has never been the opposite of learning. Free play itself is a part of deep learning. In play, children build order, experience failure, observe cause and effect, and resolve conflicts—precisely the skills we hope they learn in school. Child development experts often say: “A person who learns to take turns, negotiate, and take responsibility through play is more likely to establish healthy relationships in society.”

At the community level, an open play space is a miniature public square. It is not an isolated “facility,” but an “emotional node” that can activate neighborhood relations. In the Wall-Free Playground experiments, we often witness scenes where children naturally form small teams, set rules, and mediate disputes during play, while nearby adults transform from “watchers” into “participants” or even “collaborators.” Over time, a shared play space quietly brings more dialogue and connections, becoming a starting point for community discussion and collaboration.

Within family and social relationships, autonomous play is also a critical pathway for children to gain a sense of trust, self-identity, and belonging. A child who can freely express themselves is more likely to establish the psychological anchor of “I am accepted” in a space. This sense of security is the foundation that enables them to step into the outside world and dare to explore and take risks.

Of course, a child-perspective space is not merely “adults designing with a bit more care”—children truly participate in the design process. In our playgrounds, we have tried practices such as letting children name the equipment, graffiti on installations, sketch layouts of the space, and even inviting them to “test” adult-built structures. Children’s suggestions are always remarkably insightful. Every “naming story” or “modification suggestion” behind an installation becomes a bridge through which children form relationships with the space.

When children genuinely participate in design, they are not just building a playground; they are building a world that belongs to them. That world may not be perfect, but it is certainly authentic, engaging, and one they want to return to again and again.

4. How PlayPower Generates Well-Being for Children

“Rather than saying we built a playground, it’s more accurate to say we built an entrance to a world for children.”

PlayPower isn’t merely a set of electricity-generating play structures; it’s a new spatial language, a mode of physical and social learning: a system that enables children to actively participate, explore, express, and transform.

a. Spatial Dimension: Filling the Gaps of Absent Childhoods

On the city’s fringes and at the urban–rural margins, many children have grown accustomed to “playing in the cracks”: abandoned rooftops, narrow alleyways, small clearings among debris—seizing space in the gaps.

The modular design of PlayPower allows these overlooked corners to be rapidly transformed into “exclusive playgrounds.” Even just nine square meters can serve as a “generator” that activates the site. Children will say, “This is our place,” “Let me show you how to play”—their declaration of space: the beginning of a sense of belonging.

And the “portable” structure means that children’s rights are no longer uprooted by land expropriation, demolition, or bureaucratic approvals. A playground becomes not a fixed asset, but a freedom on the move.

b. Capability & Creativity Dimension: Play = Expression + Experimentation + Collaboration

PlayPower equipment isn’t “use me,” but “you can modify me.” From painting walls to naming installations, from “a few steps light the lamp” to “how to step more efficiently,” children’s play becomes not mere operation but a process of thinking, testing, and collaborating.

Children form “stepping teams” to take turns so the little bulb stays lit longer; they experiment with different postures on the power plate and debate which is “most energy efficient”; some even draw the power-generation process as comics, stick them beside the installation, and narrate them to adults.

Here, play is no longer just “fun,” but a “hands-on intervention” in the world. When children realize, “If I move, I can light up this place,” this small yet tangible cause-and-effect chain plants a deep belief: I have the power to change the world.

c. Climate & Civic Engagement Dimension: From Players to Public Actors

Climate issues may be abstract in textbooks, but in the world of PlayPower, they become concrete.

We design climate actions as game missions: generate enough electricity to earn an “air-purification card”; accumulate energy to light up the “village entrance billboard”; collect waste plastic to build the next installation. Children cease to be mere “spectators” of climate narratives and become “players” wielding energy and hands-on practice.

Moreover, this game mechanism isn’t closed. We invite children to propose ideas: What else can we use the energy for? Shall we hold an “Energy Exhibition”? Shall we use our generated power to host a “Nighttime Storytelling Session”?

Thus, play becomes the starting point of public events; children transform from “objects of care” into active participants, opinion leaders, and community organizers.

5. Let the “Energy of Play” Illuminate the World: The Metaphoric Power of Behavioral Energy

Play is a social energy project.

In the world of “PlayPower HappyPower,” electricity is not the focus; behavior is the energy. We treat everyone’s actions, emotions, and imagination as “energy pipelines” connected to the world.

5.1 Generating Power Through Play—and Generating Value

Within mainstream social structures, children’s behaviors are often “silent”; their running, daydreaming, and fanciful thoughts are not counted as productivity, nor seen as production. But when a child steps—and a light truly turns on, a fan starts spinning, a screen comes to life—the entire world “changes” in response to their action.

This is not symbolic; it is a “physical-level” feedback mechanism—a tangible affirmation of children’s agency and value. Adults may say, “This is just a toy,” but those with a childlike heart will say, “I can light it up”—that is the difference.

Play is no longer empty energy consumption; it is energy production.

In this sense, play becomes “useful,” and this usefulness is not about adhering to utilitarianism, but a way for the world to respond to children: when you move, the world lights up. This is a feedback mechanism for children’s sense of existence and worth—a system of energy in which “play equals affirmation.”

5.2 Behavioral Energy as a Social Metaphor for Child Well-Being

If electricity is the surface, then the true meaning behind “behavioral energy” is a metaphorical shift in social structure.

For a long time, children have been treated as “not-yet-mature citizens,” their voices, time, and choices “on hold,” waiting to be seen by society only after adulthood. But in “PlayPower,” every movement a child makes is instantly acknowledged by society, recorded in the space, and displayed by the installations. A child’s presence is “stored in real time” into the public system.

From “generating power through play” to “generating rights through play.”

This is not merely a change in play; it is a relabeling of children’s social status. Play is no longer “permitted leisure time,” but a concrete form of the right to express, the right to autonomy, and the right to participate.

When a child’s name appears on the screen of a power-generating installation, when their drawing lights up an entire community notice board, and when “how much power did you generate today” becomes neighborhood conversation, children are no longer “beneficiaries of public affairs,” but co-participants in public space.

This is the social significance of behavioral energy: transforming intangible rights into visible, tangible reality.

5.3 Creating a “Behavioral Energy Economy”: Children Not Only Generate Power but Also Master Their Own Energy World

In the world of “PlayPower HappyPower,” children do more than switch on lights; they also illuminate a small social system of their own: a “behavioral energy economy” in which they can genuinely participate, manage, and even propose improvements.

Within this system, every joule of electricity generated by jumping, running, or stepping on a pedal is logged as “energy points,” converted into PlayCoins (HappyCoin), which children can use to redeem books, stationery, art supplies, or even extra time on their favorite interactive installations.

For children in underdeveloped regions, this means that they need not depend on their families’ economic means; through their own actions, imagination, and creativity, they can earn the resources they need to grow.

PlayCoin is not just currency; it is a tool for growth.

We encourage children to plan and manage their PlayCoins themselves: Should I redeem one of my favorite paintbrushes now, or save up for a book? In this process, they are subtly introduced to financial literacy, learning weighing options, planning, autonomous decision-making, and delayed gratification.

PlayPower also offers age-appropriate financial education courses and story workshops, helping children understand the underlying logic that “my actions create value.”

Everyone can initiate a “proposal”—this is a Behavioral Energy DAO in which anyone can participate.

More importantly, in the Behavioral Energy ecosystem, each child’s idea can change the world. Whether it’s “Can we modify this installation to spray bubbles?” or “Shall we set up an ‘Energy-Saving Leaderboard’?”—as long as a proposal is adopted and used, it will earn extra rewards and collective feedback.

We are building an open, traceable Behavioral Energy Proposal System, enabling everyone to become co-creators of the rules. Adopted ideas, contributions, and PlayCoin records will be stored on-chain, becoming the “behavioral credit and public contribution value” that they start accumulating from a young age.

In this system, children are not simulating a future society; they are already living in it; they do not wait until adulthood to speak—they can be heard, seen, and respected here and now.

This is a DAO for childhood—a society of energy grounded in behavior and centered on the child’s spirit.

6. The Future of Play Requires Us to Co-Create Together

Play is the language of children, the mother tongue of all, and the covert code of society’s future.

Every Children’s Day on June 1, we’re accustomed to giving gifts and arranging performances for kids, but in fact, it ought to be a moment of collective social practice: Do we truly understand children? Have we given them the space to express, participate, and co-create?

Play isn’t just a matter for children; it concerns how we envision the future of our cities, our education, and our social structures.

Who Do We Want to Invite?

Community Residents: Join us to build a play nook for neighborhood children; let vacant lots glow and relationships flow.

Educators & Principals: Bring “play” back into schools as part of learning, not its opposite.

City Officials & Designers: Incorporate children’s perspectives into policy and spatial design so that “child-friendly cities” become the norm, not the exception.

Businesses & Brands: Transform public welfare and climate action into tangible “co-creation scenarios,” lighting up city corners together with children.

What Do We Want to Co-Create?

A forward-looking “play ecosystem” that might include:

Inclusive play spaces for all children (especially neurodivergent children, girls, and those with mobility challenges);

Child-participatory design mechanisms that make children “co-builders of space”;

Climate education and sustainable behavior prompts that let children engage in public issues through “power generation” and “action”;

Modular play units suitable for urban fringes, rural areas, post-disaster zones, and other contexts;

Behavioral energy data visualization systems that record the social significance “lit up” by each play session, making play a catalyst for broader social possibilities.

These may seem like small installations and minor changes, but behind each glowing dot lies the embodied practice of children’s rights, social structures, and the climate’s future.

Children are not tomorrow’s citizens; they are today’s collaborators.

Future energy comes not only from the sun and wind but also from childhood laughter, failure, creation, experimentation, and cooperation. Let us together become the conduits of this energy.

Let’s stay connected!

🔗 LinkedIn: [HappyPower in LinkedIn]

📸 Instagram: [@happypowerworld]

📘 Facebook: [HappyPower in Facebook]

🌐 Website: [HappyPower]

Hey, are you trying to find the HappyPower team?

Founder: Becca Liu (贝卡)

👉WeChat: OcO_OcO_OcO

👉Email: echoffline@gmail.com

👉 Whatsapp: +44(738)8912650

Comments